Return to the Stevens Family Homepage

Feb.4, 1998 -

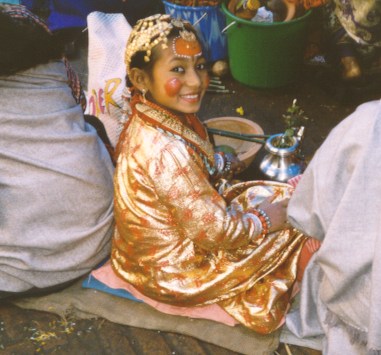

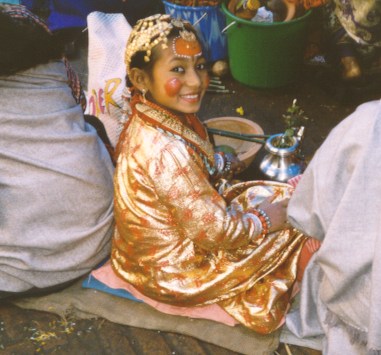

I just got back from the Pashupatinath Hindu Temple in Kathmandu. Sadhus were congregating there for an upcoming religious festival. Some were camped in caves or under shelters, speaking with passersby in decidedly English accents. A young boy sadhu with face painted in white stripes puffed on a cigarette and chatted with his elders. A trio with faces painted yellow and white sat by a temple frequented by monkeys. They had flutes and baskets with cobras which they would open only if it appeared that someone in the crowd might pay for a photo. You could see them scouring the audience for photo/cash ops. Meanwhile, riverside, a series of cremations was under way. Wood blocks (costing 1300 rupees for the stack) were piled up and spread with ghee. Bodies shrouded in orange cloth and flower petals were carried around the stack, placed on top, and set afire with kindling of straw, lighting the shrouded face first. Bare feet sticking out of one sizzling pyre blistered and swelled but managed for a time to avoid the smoke and flames of eternity.

Before coming to Nepal this winter, we had learned on the Internet of 2-degree temperatures in Katmandu with snow on the ground, and we bought whatever fleece was available in Abu Dhabi in anticipation of even harsher conditions in the mountains. On arrival, we found a balmier 16 degrees C, and plenty of trekking gear available in shops throughout the streets of Kathmandu. Days were warm and hotels had improved since I was last in Nepal in 1979. Our hotel room ac's had hot water most of the time and heaters that got us nicely through the cold nights.

We had booked our trek through Iceland Trekking & Expedition (P.)Ltd., comm@dilish.mos.com.np. This outfit turned out to be exceedingly competent and thorough in its preparations on our behalf. They collected us at the airport and held a welcome dinner for us at which the sherpas who would be accompanying us answered all our questions and provided us with brochures explaining all aspects of what we were likely to encounter in our trek, and a climbing sherpa accompanied us on trips to rent gear. Iceland Trekking would provide us with tents, sleeping bags, porters, kitchen staff, and a team of highly trained and qualified climbing sherpas, while we rented items such as down jackets, plastic snow boots, ice picks and ski poles, and climbing harnesses and jumars ourselves. They had suggested the Langtang area for our trek and a peak we might like to ascend while there, and they reassured us with their apparent command of logistics in arranging for us to reach out goal.

Our destination would be the 5846 meter peak of Naya Kanga. The most volatile variable in the equation was how each individual would react to altitude, which would increase gradually during the trek, at the recommended rate of 400 meters a day once we passed 3000. As it turned out, in our original group of 8, one couple would turn back at 3800 meters with a case of AMS (acute mountain sickness) while another of our party went no higher than that same altitude. AMS was the fear of all in our group, the topic of much conversation, and most members of our expedition took diamox to combat it. I was perhaps more confident than the rest, having been to the top of 6000 m. Kilamanjaro 25 years previously, so I didn't take any diamox. Still, it's hard to know what one's body will do after 25 years, so I took it easy on the way up and tried not to push my luck.

On the morning we set out from Kathmandu, Iceland Trekking arranged a bus for us that caused one member of our group to comment, "I can't image that this bus was ever new, ever." Almost all buses are like that in Nepal, not to mention almost everywhere in the third world. Our bus even broke down a couple of times en route but was always repaired either temporarily by the roadside or more permanently in towns where we took prolonged breaks. We made our way out of the Kathmandu Valley along remarkably terraced hillsides to Trisuli Bazaar and then on to the larger town of Dhunche where the road bifurcated to Bharku and Syabru Bensi (Lower Syabru) where the road essentially ended and we would begin our trek. The last bit of road was marked 50 km to Syabru and took forever, winding in and out of traverses across mountainsides. Despite having been driving since early morning, we arrived in Syabru Bensi after dark and had to descend to the riverside where our camp was set up for us in the chill evening. We settled into sleeping bags, testing them for warmth, and got used to our tent-mates, in most cases a spouse.

In the morning, we were awakened at 6:30 in a dawn chill countered with hot tea brought to our tent, followed by a bowl each of hot wash water. Thus we began a routine that went on for the next 10 days. After the ritual of morning-tea-in-bed, we would pack up our bedrolls and assemble for breakfast either in the dining tent or al fresco, depending on whether the sun or wind had reached us by then through the mountaintops. By eight or nine we were usually on the trail, and we would go for 3 or 4 hours to our lunch spot, with occasional stops at tea houses spaced along the trail up Langtang Valley. The Nepalese government managed the land along the river, the Langtang Khola, as a national park. They had had simple coined-stone lodges build along the route and arranged for homesteading families to run them. The families tended to be welcoming to all comers, and would fire up a stove in the middle of a room for evening warmth in exchange for beer purchases. All beer, and everything for that matter, had to be trekked in here. We would stop at such places for lunch and our staff would take over a building and perhaps a fireplace for tea and food preparation. Lunch would be very relaxed, lasting a couple of hours, followed by an afternoon trek to our night campsite, which again would be on the grounds of one of the locally run lodges. When our porters would catch up with us (one porter carried at least three of our packs), our tents were erected and a latrine tent would be pitched around a shallow hole. We would be brought hot tea or lemon drink as dusk fell and we added clothes against the rapidly ensuing chill. As the kitchen staff assembled off the trail and got its act together, dinner would follow. There would then be more tea, and except at the higher altitudes where we all realized we needed to avoid alcohol, there was usually beer. There was not always a fire, so we would typically retire early to our tents and sleep for nine or ten hours a night. Sleep was one luxury on our trek that we were always too cold and too tired not to indulge in.

The scenery in the valley reminded me of that of Yosemite, with similar raw nature and vegetation. The Langtang Khola, which we followed constantly upstream, was a raging torrent graced with ice sculptures at its higher reaches. The trail was a fine one with steps at its most difficult gradients. We climbed a lot of these steps the first day. We lunched at a lodge appropriately called Bamboo, where our sherpas cut walking sticks of bamboo for those who had not rented ski poles in Kathmandu. The attractive young Nepali hut-wives there were very industrious with weaving, working from looms strapped taut at their wastes. A belt could take a day to make and cost a couple of dollars. From Bamboo that afternoon we pushed upstream all the way to Lama Hotel just below the 3000 meter mark. By now we had caught our first glimpse of the really high snowy mountain peaks up the valley from us. Lama Hotel was a collection of lodges cloned from the "original" which meant nothing to us who were there for the first time. After a beer or two and a dinner of dhal-bhat, we cuddled into sleeping bags whose layers we re-calibrated against the slightly greater cold.

We were reassured that our 2nd day of trekking would be a more gradual climb to the settlement of Langtang, but to me it was more difficult than the first, probably due to the altitude effect. By the time we had made our lunch stop at Ghore Tabela, a narrow meadow at 3048 meters near the base of a wide gorge, I was ready for a nap on the lee side of a crisp grass knoll. After lunch we had a climb of another 300 meters to Langtang. I recall being so tired at the end of the day that it required major effort to get myself from the first lodge we encountered to the one we were actually camping at just a hundred meters up the trail. When I finally made it to a resting spot I was offered a beer but refused it, which must have been indicative of an altitude effect. Langtang was also known for funneling the wind in off the mountains, so we spent a cold night there and had an especially cold wind-whipped breakfast barely sheltered by our dining tent next morning before the sun could crest the surrounding snowy mountains.

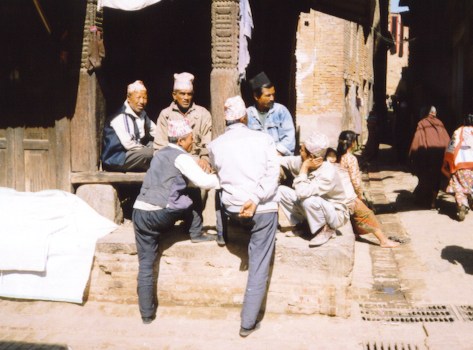

Our 3rd day out provided us a much easier ramble up from Langtang to Kyangjing Ghomba, where there was a derelict monastery, a yak (technically nak, female for yak) cheese factory closed for the winter, and the last set of lodge buildings at the trailheads leading into the high mountains. Kyangjing Ghomba was occupied mainly by people from Langtang who operated the lodges and cheese factory as their business, and the people of Langtang were in turn largely Tibetan refugees from just over the snow-peaked border. The mix of cultures was more evident here than at lower altitudes. The Tibetans had artifacts arrayed on crude tabletops, somehow more appealing here than when seen cluttering shops in Kathmandu. The walk from Langtang to Kyangjing Ghomba was along a trail set with mani stones, shale slates carved with prayers and renditions of Buddhas and mandalas and set in sturdily constructed rows in the middle of the trail. The mani stones stretched for kilometers and had to be walked around always on the left. Along the way there were lodges closed for the winter with the only sign of habitation being smoke from people's houses set at the edge of fields graced with yaks (and naks) and sheep and goats. Children would approach asking for chocolates and "school pens" and ladies and gentlemen we encountered in the road would say "namaste" through ruddy visages. The women in particular were colorfully dressed, the married ones wearing colorfully woven blanket-skirts secured with a gold belt. Most local people on the trail were bowed under prodigious burdens of household goods or wood cut illicitly (green) from the jungle.

We got into Kyangjing Ghomba after only a couple of hours walking and were put up in one of the lodges rather than set up tents, which would have required shoveling the snow which lay thick here on the ground. After such a short walk, a few of us were hot to hit the hills, though we were cautioned to take it easy by Tenze, our head sherpa (sirdar). Four of us walked up to the monastery and pushed the ridge a little ways beyond, but the going proved too snowbound for us to continue far that way. I forced my way uphill on my own, my companions having elected to plod back the way they had come. I wanted to gain a little altitude and I had seen patches of ground where there was no snow, so I got myself with a great view of the settlement of Kyangjing Ghomba and the snowy peaks beyond the valley we had just walked up before coming down to join the others at 3800 meters.

The mountain most clearly visible across the valley was Naya Kanga, the one we meant to climb. We looked up at its formidable snowy slopes and listened to our sherpas explain how we would walk up a few hundred meters and establish a base camp just there, and then move to a high camp the next day, and the following morning make our assault on the peak and return to Kyangjing Ghomba the same day. This program seemed to be stretching it a bit to some members of our group, one of whom in fact woke up sick the 4th day, and after a climb to some prayer flags set on the lowest nearby peak at 4000 meters, decided he'd been hit with AMS and with his wife beat a retreat back to Langtang. He took this decision before the rest of us got back down off our exercise hike and most of us didn't see the two of them again until back in Kathmandu.

Meanwhile, three of us pushed that day beyond the 4000 m. peak to the next ridge up at around 4300. All the while we were entertained by sounds of avalanche on the higher reaches of the two glaciers that comprised a part of our scenic view, and by pinpoint views of our climbing sherpas on the opposite side of the valley where they had gone to check the snow conditions and leave ropes for our Naya Kanga assault. These sherpas were moving rapidly up the mountain, but the three of us were just exercising our legs at altitude, trying to stay as long as possible above the 4000 m. level. We walked the ridge line until it looked like it would push us up another quantum in altitude and then headed instead down through a snowfield that would have made an excellent green ski run back in the Sierra Nevadas. The going was a little damp and decidedly rocky, but we lost altitude quickly and got back to shelter well before the dark and accompanying cold set in.

The tireless sherpas came back to report that the snow was too deep for a base camp on Naya Kanga, and this caused Tenze, our sirdar, to shift our goal to Yala Peak, slightly lower than Naya Kanga at 5500 meters, but "easy" according to Tenze. This was agreeable to our group because the choice of peak had been made not by us but by our trek organizers, and it was agreeable to our climbing sherpas despite the fact that next morning they had to run back up in the snow to retrieve the ropes they had left on the slopes of Naya Kanga and then catch us up on the equally steep slopes of Tcherko Ri, which we had decided to summit in a more advanced training exercise. Tcherko Ri was a mere 5033 meter peak in the shape of an inverted bowl, and it looked as we started out our 5th day that it would be another day where we would push our limits as successfully as in days past. The idea in fact was to further extend our altitude range while giving us training in ropes, crampons, and ice picks, and so we were carrying harnesses and the other paraphernalia in our day packs. Had all gone well, we would have summitted Tcherko Ri while being shown the use of these items and then moved on to our base camp for Yala, which our porters and kitchen staff were meanwhile shifting to. But all did not go well.

One unexpected factor was the effect of altitude on our pace and stamina. Walking uphill proved exhausting above 4500 meters, and our upward progress was a disappointment to our sherpas, especially as two had by then caught up with us having already returned from retrieving the ropes from the day before. Another factor was snow. After 4 days of almost ideal winter weather, cloud had moved in, and fine snowfall began to freeze up the trails. We were moving slowly and conditions were worsening, so our sherpas rigged a fixed line for us as high up the mountain as we could manage in a morning and let us practice on that before ordering everyone to make for base camp without summitting Tcherko Ri.

So rather than go over the top of Tcherko Ri and come down on our base camp at 4800 m, we were faced with an afternoon of seemingly endless traverses, all heading us gradually uphill. It is difficult to describe this stage of the trek, except to say that at this altitude, time is needed for acclimatization, and if this time element is compromised, then the body just ceases to respond to the will to push it. Each step was a major effort on the traverses, all of which lasted for an hour and a half. At the last traverse we rounded a corner and in visibility decreasing rapidly as the weather closed in, we could see a set of figures making their way up the last slope leading to our campsite, dauntingly far uphill from where we were. The walk from this point was a near impossibility. The snow had piled to where many of our steps led into snow banks, extrication from which further taxed our energy and left us gasping. I found I could just about go 20 steps at a time, and sometimes I would slip at the end of that set, even that many steps being too much. The walk uphill became excruciatingly interminable. Toes were beginning to freeze. Progress was tedious. Still, the mountain ahead was starkly, coldly beautiful.

In the midst of this appears one of our kitchen staff carrying a pot of hot lemon and cups for all. He works his way lightfootedly down the line of trekkers who regard him as a savior just stepped off a cross. To each he pours a cup of hot liquid, refueling each for the rest of the grim work of achieving the tents still tantalizingly far uphill at this excruciating rate of travel. And then he strolls back up to camp. Even Tenze has tired of holding himself back and has moved casually uphill to warmth and shelter, leaving his charges struggling breathlessly up the freezing slope. Meanwhile, I've cut myself back to maybe five paces at a time. The snow is whipping in my eyes and clutching at my waterproof clothes. At length I reach the stone shelters where the kitchen staff are at work, but I still have 5 minutes to go to move 20 meters to my tent. I make it at last and ease inside, shedding wet snowboots first, changing out of wet socks and jeans, getting into dry fleece from bags the porters have left in my tent, spreading out my two bedrolls, pissing in my water bottle (no way I'm going back outside), snuggling into my fleece bedroll liner, accepting the hot tea as it's passed in the door, the same for soup to follow.

It was a bit incredible forcing one's tired freezing body to that point and then slipping into a warm tent erected by one's staff, who then brought food and warm drink. Steve, my tent-mate, had already worked his way into his cocoon, and at some point we refused further food and settled into early sleep. Temperatures outside our tent reached 20 below zero Centigrade that night, but inside the tent and bedrolls inside it was toasty warm. I had on thick woolen socks, thick fleece leggings and pullover, a fleece bedroll liner, and a down sleeping bag stuffed inside a waterproof one. I was warm and slept an exhausted sleep. Since it was my first night ever in such conditions, I made one mistake. I left clothes and other items outside packs and in the morning they were not only wet but frozen since condensation inside the tent froze into a crisp layer of frost on anything exposed. This included my hair, though I corrected the situation with a wool cap once I realized what was going on.

We were due to awaken at 3:00 a.m. for a 4 o'clock start on our 6th trekking day, but the morning tea wasn't served until nearer 4:00. I had awakened at 3:00 nonetheless but not budged from my sack. I had assumed that conditions were possibly too adverse for us to continue that day, and I thought perhaps we were not being awakened on purpose and would have a lie-in instead. I had even mentioned to Steve the night before that I didn't think we should attempt the summit the following day as planned, but all 5 of our group were spread in three tents and in no condition to get out of them, so there was no communication of this idea beyond Steve. I wanted instead to have a rest and acclimatization day, and I doubted my own ability to continue up the mountain before dawn after barely 8 hours of rest. But before 4 the wakeup call came with hot tea followed by hot soup as we packed and readied ourselves for the elements.

Outside, with wind chill factored in, the temperature was 30 below. In the tents, Steve and I struggled to get into our snow boots. They had frozen up during the night and wouldn't flex at all. I had just put on my frozen wet blue jeans though I was able to replace my wet socks. I soon met my friends outside, each with a caving lamp on the head. All had on waterproofs against the wind driven snow, but no one had put on a down jacket.

We plodded up the mountain in the dark, Steve and I following close behind Tenze. Steve stepped where Tenze did and I stepped in both their footprints. Occasionally, Tenze would bog down in snow and alter direction to find firmer footing, and then Steve and I would wait for him to recover and take advantage of his course correction. Now and then I would look around to see the snow dark in the moonlight except for the tops of the peaks which jutted ethereally against the star dark sky like inverted icicles on the high horizons. Tenze seemed off his usual mark. At some point we stopped him to point out that the others were far behind, and he admitted he had lost the track in the blinding snow flurries. We stopped to wait and I tried moving my fingers and toes to try and thaw them. When we moved on, it was to stumble on in the dark, one step up for each step bogged in deep snow.

Dawn came as we shuffled up the mountain. With the light and added altitude we could better appreciate the scope of what we had undertaken as we rose gradually above base camp, but we could see also how far we had to go. Still we tackled each slope at the best pace we could muster, which was painfully slow for our sherpas, who were starting to wait for us on outcrops and then move off as we drew even with them so as to hurry us on with minimal rest. We knew we had to move but we could only do so only small steps at a time, like the day before.

As the sun rose, the snow gradually ceased to blow around us and the edge came off the cold. I stopped on a slope to take off outer garments and managed to let my camera slip in the snow. It started down the mountain like a sled out of control. One of the sherpas, a 19 year-old kid the same age as my oldest son, darted over to head it off, wielding his walking stick like a harpoon. I could hardly move up or down myself and could only admire his alacrity as he saved my camera and brought it spryly back uphill for me.

Another indication of our lack of fitness for altitude climbing came in the form of some Americans camped near us. One of the ladies among them was a climbing instructor. They started up Yala peak an hour after we did and by midmorning had passed us. When we eventually quit our effort, they were scaling the ice near the top, about to achieve the summit in an easy morning's outing.

By about 11 we pulled ourselves up to a level spot which Tenze said was at 5250 meters. We were spent forces by then, and Tenze expressed concern that the "easy" walk he had anticipated would take 5 or 6 hours had taken that long already and, if we went no faster than we were going, would take that long again to complete, and leave us returning to base camp in the dark. In our group, three of us had been training for a mid-February marathon, running 15 and 20 kilometer runs on Mondays and Wednesdays every week in the month prior to our venture to Nepal, but this training was done at sea level, and at altitude we were simply not fit without some days spent acclimatizing. On that day, we weren't going any faster, and we came to the conclusion as a group that 5250 meters was enough of an achievement, and could we go home now.

And basically, that was it. The trail back down to base camp wasn't much easier than the way up since we still had to deal with deep snow, but food, warm drink, and warm sunshine awaited us as we rested while the porters wrapped up the camp for the trek back to Kyangjing Ghomba, which we reached just before nightfall. Now that we were heading down, we could drink beer; plus we had worked out an arrangement with the lodge owner whereby he would build a fire in his stove if we paid the fine to the police, around $4 per infraction. And on this night, we got one of the locals to admit that he could dance if he could drink a beer or two first, so we primed him, and he arranged for his friends to join him in some Tibetan song and dance. This was a pretty weak show as Tibetan music goes, but it broke the ice with our sherpas and porters, who prepared a more elaborate festival for the following night.

We planned a leisurely route down off the mountain, retracing our steps most of the way. A couple of our group had developed blisters, and one lady was stiff from days of protracted walking, so we eased way back on the pace. This in turn lightened the load on the porters and kitchen staff who began looking forward to an easy end of trek. Our first day out of Kyangjing Ghomba, our 7th day of trekking, we planned a lunch stop at Ghore Tabela but ended up enjoying the clear mountain air and spending the night there. On the way there, we had stopped off at the monastery above Langtang and meandered down hillsides spread with yaks before picking up the trail alongside the roaring river. Our 8th day out carried us downhill to Lama and into the stone steps beyond, much easier going down, until we reached Rimche where we had seen lemur monkeys on the way up. There were no monkeys in the hills this time, just yaks and goats, but the lodge owner had a homemade violin which someone played while we ate lunch. And then we followed the wildly plunging river on to Bamboo where we took over a lodge with yet another stove while the tents were erected and our dinner prepared. Next morning we pushed on in our 9th day dropping down to the river bed before climbing back up several hundred meters to the town of Thulu Syarabu, 2500 meters at the top of a hill worked with terraces, where we had lunch in the chill induced by sudden lack of sun. After lunch we pushed on in intermittent rain over the mountain and down the other side to Bharku, where we met the road and camped one last time. A bus was there to meet us, arranged by the ever-efficient Iceland Trekking (P)Ltd people, but due to the condition of the road, it would not leave until the following day to return us to Kathmandu.

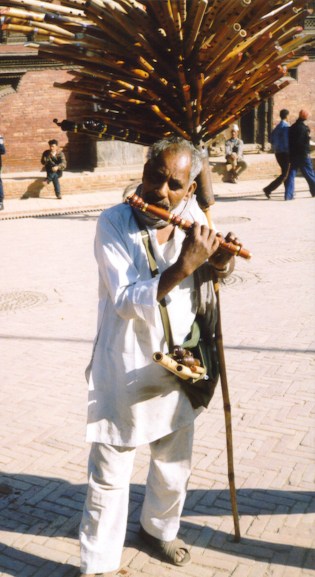

One of the most interesting things about the return journey was the musical events put on by our sherpas and porters. The people in the valley shared a common heritage of song and dance, so that if one person picked up a flute, another would answer with a drum, or if men sang a chorus, women who had gathered from the village might answer with a verse of their own. We could hear our staff prepare for these events while doing the camp chores, and eventually they would join us en masse. These soires turned into big events, with all of us required to strut a dance as best we could. The music served to develop a sense of solidarity in our group and fostered genuine friendliness among us, and at the town of Bharku, where the townsfolk joined in, the deep richness of the culture that the music tapped was most apparent. This continued in Kathmandu where we spent an evening at a dance performance put on for tourists, but could further appreciate the rhythms and dance moves in the perspective of what we had experienced in the field.

All in all it was an invigorating holiday spent in the company of the gentle and sharing people of Nepal, who went out of their way to show us their mountains and their country, providing us much more in service and amenities than we felt was strictly necessary for what we had paid.

A friend comments:

I just read your trip account from the Nepal trip, it sounds like a lot of fun, and pretty tough. I dunno it seems like cheating to me though to have someone else carry all your stuff and serve you hot tea in your sleeping bag (not that I wouldn't mind having someone do that sometimes 8-)!

I reply:

Cheating? Yeah, in a way. Having porters was an interesting aspect of our recent trek that I'd never experienced before. For one thing, you find that you take everything under the sun that you think you might need. Weight is after all no object, and doesn't seem to be for the porters, who carried three of those bulging packs each, up a 4000 meter altitude gain, and at the higher altitudes outpace the clients. For 8 climbers, we employed about 30 people for 12 days: sherpas guides and climbing experts, cooks and porters. These people did their job with a spirit of comradie that rubbed off on the clients. I mean, they were really friendly. In fact, we were especially impressed with the sense of community shared by the people we hired and the people living in the mountains; there was never a note of discord that I witnessed among any Nepalis in the 2 weeks we were there, and we were treated like guests and not as "pax". The whole trek cost each of us $500, and that included almost all meals and 5 nights in a decent hotel in Katmandu, not to mention all the services rendered in ten days actually trekking. Even when we got back to Katmandu, our guides hung out with us and arranged minibuses to take us around the other towns in the valley. They were really great. I really recommend that kind of trek. And of course the sherpas were indispensible at the higher altitudes, and allowed us the reassurance that we would not freeze in the extreme weather conditions despite our reduced stamina at altitude. So if you get the chance, go for it.

Latahs,

Vance

Visits since February 6, 1998 -:

Use your browser's BACK button

to return to a previous pageFor comments, suggestions, or further information on this page, contact Vance Stevens, page author and webmaster.

This page hosted by ![]() Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page